The most common failure issues of nail screws and other fasteners fall into three main categories: mechanical failures such as head stripping (cam-out), shearing, and thread damage; environmental failures like rust and galvanic corrosion; and installation-related errors, including over-tightening and improper hole preparation. Understanding the causes behind these problems is critical for professionals in manufacturing, construction, and engineering to ensure the safety, integrity, and longevity of their assembled products and structures. Choosing the right fastener and installing it correctly can prevent costly repairs, product recalls, and catastrophic structural failures.

Screws are the unsung heroes of countless applications, from micro-electronics to massive skyscrapers. Yet, when they fail, the consequences can be severe. This guide provides an in-depth look into why screws fail, how to diagnose the issue, and most importantly, how to implement preventative measures. By focusing on material science, proper installation techniques, and quality sourcing, you can mitigate nearly all common fastener issues. At RivetJL, we believe that an educated partner is a successful partner, and this knowledge is the first step toward building more reliable and durable products.

Understanding the Root Causes: Why Do Screws Fail?

Screw failure is rarely a random event. It’s almost always a result of a specific stress or condition exceeding the fastener’s designed capacity. These causes can be broadly classified into mechanical issues, environmental degradation, and manufacturing defects. By identifying the type of failure, you can trace it back to its root cause and prevent it from happening again. A sheared screw tells a different story than a rusted one, and learning to read these signs is a crucial skill for any technician or engineer.

Mechanical Failures: The Physical Breakdowns

Mechanical failures are the most immediate and often dramatic types of screw issues. They occur when the physical forces exerted on the screw—either during installation or during its service life—surpass its material strength. These are often preventable with proper selection and technique.

Shearing and Tensile Breakage

Shearing occurs when forces are applied perpendicular to the screw’s length, causing it to snap clean across its shank. Tensile breakage happens when the screw is pulled apart along its axis, exceeding its ultimate tensile strength. Both are critical failures that result in a complete loss of clamping force.

- Causes: The primary cause is applying a load that exceeds the screw’s specified capacity. This can be due to a design miscalculation, an unexpected shock load, or using a screw made from an inadequate material grade (e.g., using a standard steel screw in a high-stress application requiring a Grade 8.8 or higher). Over-tightening can also pre-load the screw close to its breaking point, leaving little capacity for operational loads.

- Prevention: The solution begins with proper engineering. Always calculate the expected shear and tensile loads and select a screw with a strength rating that provides a sufficient safety margin. Use materials appropriate for the application, such as hardened alloy steel for high-load scenarios. Ensure that installation torque is controlled with calibrated tools to avoid over-stressing the fastener from the start.

Head Stripping (Cam-Out)

Cam-out is the frustrating process where the driver bit slips out of the screw head’s recess (e.g., Phillips or Robertson) during tightening. This damages the recess, making it difficult or impossible to drive the screw further or to remove it later. It is one of the most frequent installation-related failures.

- Causes: The most common causes are using the wrong size or type of driver bit, applying insufficient downward pressure, or driving the screw at an angle. Low-quality screws with poorly formed recesses or soft material are also highly susceptible to stripping.

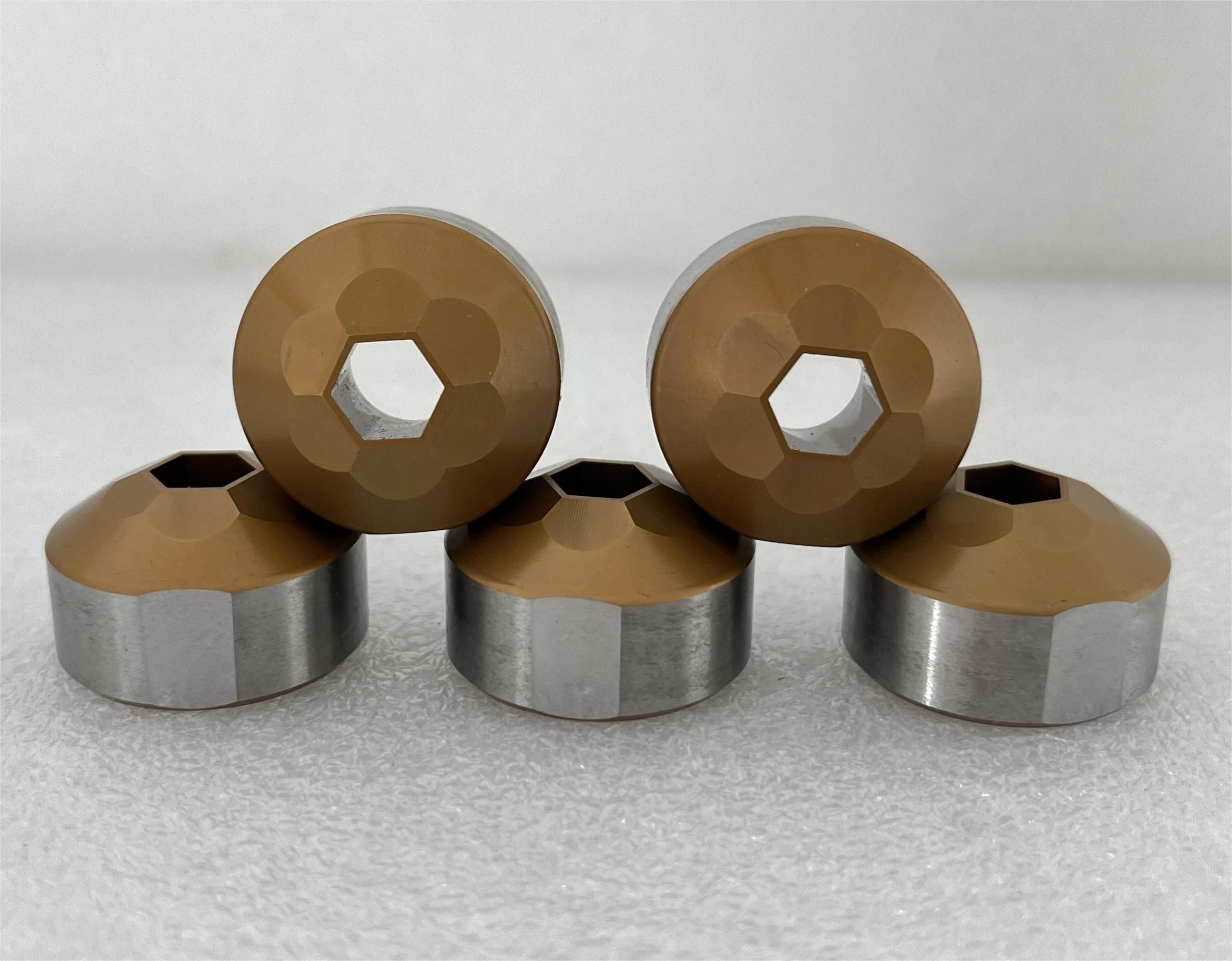

- Prevention: Use a high-quality, correctly-sized driver bit that matches the screw head perfectly. Drive systems with better engagement, like Torx (star) or hex sockets, are inherently more resistant to cam-out than Phillips heads. Apply firm, consistent axial pressure during installation and ensure the driver is perpendicular to the screw head.

Thread Stripping

Thread stripping happens when the screw’s threads or the threads of the mating material (the nut or tapped hole) are deformed and stripped away. This is common when a steel screw is driven into a softer material like aluminum or plastic, or when a fine-threaded screw is over-torqued.

- Causes: Over-tightening is the number one cause of thread stripping. It applies a force that exceeds the shear strength of the thread material. Cross-threading, where the screw is inserted at an angle, can also initiate thread damage that leads to stripping under torque.

* Prevention: Use a torque wrench or torque-controlled driver set to the manufacturer’s specifications for the fastener and mating material. When driving into soft materials, consider using screws with coarser threads or using a threaded insert to provide a stronger mating surface. Always start screws by hand for the first few turns to ensure proper alignment and prevent cross-threading.

Corrosion Failures: The Environmental Attack

Corrosion is a slower, more insidious form of failure caused by a chemical reaction between the screw material and its environment. If left unchecked, it can weaken a fastener to the point of mechanical failure.

General Rust (Oxidation)

This is the familiar reddish-brown coating that forms on iron or steel-based screws when they are exposed to oxygen and moisture. Rust not only looks unsightly but also degrades the material, reducing the screw’s cross-sectional area and compromising its strength.

- Causes: Exposure to water, humidity, salt spray, and other corrosive chemicals without an adequate protective coating. Standard, uncoated steel screws are extremely vulnerable.

- Prevention: The best defense is material selection and coating. For outdoor or damp environments, use screws made from stainless steel (Grades 304 or 316) or use carbon steel screws with a robust protective coating, such as hot-dip galvanization, zinc plating, or a specialized ceramic coating.

Galvanic Corrosion

Galvanic corrosion is an accelerated form of corrosion that occurs when two different types of metal are in electrical contact in the presence of an electrolyte (like saltwater). The more “noble” metal will cause the more “active” metal to corrode at a much faster rate. A classic example is a steel screw used to fasten an aluminum plate, which will cause the aluminum around the screw to rapidly deteriorate.

- Causes: Joining dissimilar metals without proper isolation. The severity depends on how far apart the metals are on the galvanic series.

- Prevention: Whenever possible, use fasteners made of the same or a galvanically compatible material as the parts being joined. If dissimilar metals must be used, isolate them with non-conductive plastic or rubber washers and bushings. Alternatively, choose a fastener material that is noble to the materials being joined (e.g., a stainless steel screw is safer for a steel plate than an aluminum screw would be).

Manufacturing & Material Defects: Problems from the Start

Sometimes, a screw is destined to fail before it’s even taken out of the box. Defects introduced during the manufacturing or plating process can create hidden weaknesses that lead to unexpected failures under normal operating conditions.

Hydrogen Embrittlement

This is a particularly dangerous defect that affects high-strength carbon and alloy steel screws (typically Grade 8/8.8 and higher). During manufacturing processes like acid cleaning or electroplating, hydrogen atoms can be absorbed into the steel’s crystal structure. These atoms make the metal brittle, leading to sudden, catastrophic failure hours or even days after being tightened, often with no visible warning.

- Causes: Improper manufacturing and plating processes that introduce hydrogen without a subsequent baking process to drive it out.

- Prevention: This is almost entirely a quality control issue. Source your critical, high-strength fasteners from a reputable supplier like RivetJL who can provide documentation and certification that proper hydrogen embrittlement relief procedures (baking) were followed as per industry standards (e.g., ASTM F1941).

How Installation Errors Lead to Screw Failure

Even the highest quality screw can fail if installed incorrectly. Proper technique is just as important as proper selection. Many failures blamed on the “screw” are actually due to the “screwdriver” or, more accurately, the person operating it.

Over-Torquing: This is the most common installation error. It can cause immediate thread stripping or tensile breakage. Even if the screw doesn’t break immediately, over-tightening can stretch it past its elastic limit (yield point), permanently weakening it and making it susceptible to failure from vibration or shock loads.

Under-Tightening and Vibration: A screw that isn’t tight enough doesn’t provide the necessary clamping force to hold an assembly together securely. Under load and vibration, an under-tightened screw can loosen completely, or it can be subjected to repeated cyclic stresses that lead to fatigue failure over time.

Improper Hole Preparation: The size of the pilot hole is critical. A hole that is too small can cause the screw to bind and break during installation. A hole that is too large will not allow the threads to engage properly, resulting in low holding power and easy thread stripping.

A Proactive Approach: How to Prevent Common Screw Failures

Preventing screw failure is a holistic process that involves careful planning, correct selection, and meticulous installation. By adopting a proactive mindset, you can virtually eliminate these common issues.

The following table summarizes the primary failure modes and the most effective prevention strategies.

| Failure Type | Primary Cause(s) | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Shearing / Breakage | Load exceeds material strength; over-torquing. | Select higher-grade material; use a calibrated torque wrench. |

| Head Stripping (Cam-Out) | Wrong driver bit; insufficient axial pressure. | Use correct bit size; use Torx/Hex drive; apply firm pressure. |

| Thread Stripping | Over-tightening; cross-threading. | Control torque; start screws by hand; use threaded inserts in soft materials. |

| Rust / Oxidation | Exposure to moisture and oxygen. | Use stainless steel or screws with zinc/galvanized/ceramic coatings. |

| Galvanic Corrosion | Contact between dissimilar metals. | Use compatible materials or isolate with non-conductive washers. |

| Hydrogen Embrittlement | Improper manufacturing/plating of high-strength steel. | Source from trusted suppliers with certified quality control. |

Sourcing from a Trusted Supplier

Perhaps the single most important preventative measure is partnering with a knowledgeable and reputable fastener supplier. A quality supplier does more than just sell parts; they act as a technical resource. They understand the nuances of material grades, coatings, and manufacturing standards. By working with an expert partner like RivetJL, you gain access to a team that can help you select the precise fastener for your application, ensuring you have the right material, strength, and corrosion resistance. This partnership mitigates the risk of receiving counterfeit or poorly manufactured parts and provides peace of mind that your assemblies are built on a foundation of quality.

Conclusion: Building Durability Starts with the Right Fastener

Screw failures are complex, but their solutions are often straightforward. By understanding the forces and environments your fasteners will face, you can make informed decisions about selection and installation. From preventing the immediate drama of a sheared screw to stopping the silent attack of corrosion, every choice matters. Remember that a screw is not just a commodity; it’s a critical engineering component. Investing in the right fastener and the knowledge to use it correctly is an investment in the quality, safety, and reliability of your final product.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What is the difference between a stripped head and a stripped thread?

A: A stripped head (cam-out) refers to damage to the drive recess on the top of the screw, making it difficult to turn. A stripped thread refers to damage to the helical ridges on the screw’s shank or in the mating hole, which prevents the screw from holding tight.

Q: Why do my stainless steel screws sometimes rust?

A: While highly resistant, not all stainless steel is completely rust-proof. Lower grades like 304 can show surface rust in harsh marine environments. Contamination with plain steel particles (e.g., from steel wool or tools) can also cause spots of rust to appear. For maximum resistance, Grade 316 stainless steel is recommended.

Q: How do I know how tight to make a screw?

A: The ideal tightness, or torque specification, is determined by the screw’s size, material grade, and the materials being joined. Manufacturers and engineering standards provide torque charts for specific fasteners. Always use a calibrated torque wrench for critical applications to ensure you are within the specified range, avoiding both under-tightening and over-tightening.